Research reveals that the ecological adaptability of humans, honed within diverse African habitats, was pivotal for their successful migration out of Africa around 50,000 years ago.

Early human history remains unclear to this day. How, when, and why humans expanded from Central Africa is a difficult puzzle to solve as intact archaeological records can be few and far between. However, discoveries of tools we used, related hominims, and places we used to live in, are gradually uncovering what life was like for our ancestors. In the last year alone, we have found that early Homo sapiens may have lived at first in dense, humid, jungles, and that interbreeding was more common than we have ever predicted. Exploring the early journey of humanity is still one of the greatest scientific endeavours, and a central question to our existence.

Findings from a recent study has revealed that around 70,000 years ago, Homo sapiens experienced a significant expansion in their ecological niche within Africa, long before their successful dispersal from the continent approximately 50,000 years ago. This expansion allowed early humans to adapt to a diverse array of habitats, from dense forests to arid deserts, showcasing a remarkable ecological flexibility that likely set the stage for their eventual global colonization.

The fascination with how modern humans came to inhabit varied environments around the world has intrigued scientists for years. While genetic evidence indicates that all contemporary non-African populations trace their ancestry to a small group that left Africa about 50,000 years ago, fossil records point to earlier migrations that were less successful. This begs the question: what factors enabled the later dispersal to succeed?

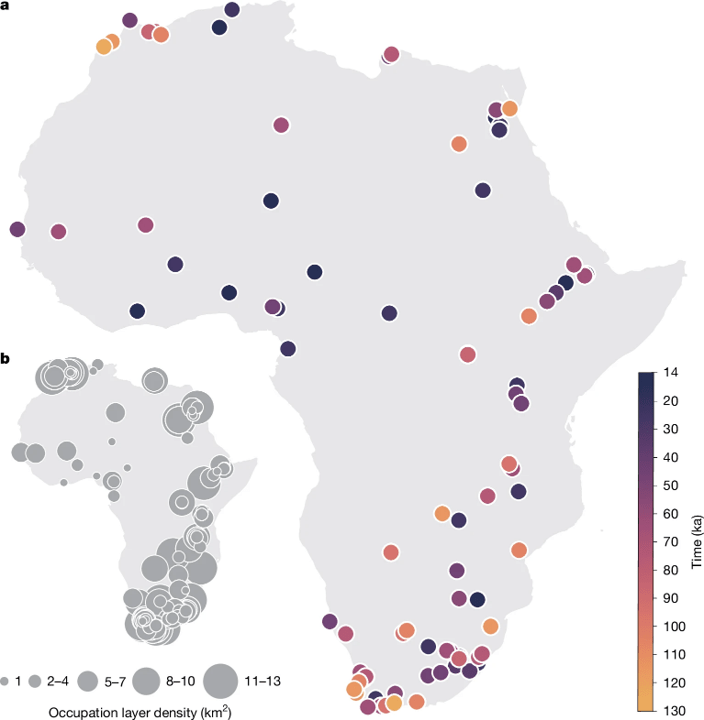

Published in Nature in 2025, the study led by Emily Y. Hallett and her team from institutions such as Loyola University Chicago, the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology, and the University of Cambridge, aimed to answer this question. The international research team compiled a comprehensive database of 479 radiometrically dated archaeological sites spanning from 120,000 to 14,000 years ago. Using species distribution models (SDMs) and advanced statistical techniques, they quantified changes in the bioclimatic niche of early humans over this period.

The researchers focused on five key environmental variables: leaf area index (which measures vegetation density), temperature ranges, and precipitation during the wettest periods. By integrating these variables with paleoclimate simulations, they reconstructed the suitability of various African habitats for human occupation through time. To assess whether the human niche changed over the millennia, they applied generalized additive models (GAMs).

Their analysis revealed a significant increase in the habitable geographic range of Homo sapiens starting around 70,000 years ago, particularly in West, Central, and North Africa. This expansion aligned with Marine Isotope Stage 4, a time characterized by climatic fluctuations. A second, broader expansion occurred around 29,000 years ago during Marine Isotope Stage 2. These expansions were driven not only by climatic changes but also by an increase in the diversity of habitats utilized by humans, including forests, savannahs, and deserts.

Key statistics underscore this trend: the number of archaeological occupation layers saw a substantial increase in more recent periods, indicating a growing human presence; niche breadth expanded notably from 70,000 years onward; and the spatial range of suitable habitats within Africa grew significantly, highlighting enhanced ecological flexibility.

However, the archaeological record is uneven, with preservation bias favoring more recent sites and some chronological uncertainties in dating layers. The researchers addressed these issues by subsampling data to ensure temporal consistency and using robust statistical models, but inherent uncertainties in reconstructing deep-time human ecology remain.

These findings have significant implications. They suggest that the successful migration out of Africa around 50,000 years ago was facilitated by humans’ prior ecological adaptability within Africa, allowing them to thrive in a variety of challenging environments. This ecological flexibility likely provided the resilience needed to colonize new and climatically diverse regions beyond Africa.

The study reshapes our understanding of human evolution by highlighting the importance of niche expansion and habitat versatility in our species’ dispersal success. Rather than attributing this success to a sudden technological or cognitive leap, it emphasizes that a gradual broadening of ecological tolerance laid the groundwork for humanity’s global journey.

Why it matters.

By emphasizing the importance of niche expansion, the results of the study changes our understanding of human evolution, highlighting gradual ecological flexibility as the key to global colonization! We still have so much to learn about human history and the effects of the environment.

References:

Study:

Hallett, E. Y., Leonardi, M., Cerasoni, J. N., et al. (2025). Major expansion in the human niche preceded out of Africa dispersal. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09154-0

Further Reading:

- Scerri, E. M. L., et al. (2018). Did Our Species Evolve in Subdivided Populations across Africa, and Why Does It Matter? Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 33(8), 582-594.

- Stringer, C. (2016). The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 371(1698), 20150237.

- Harvati, K., et al. (2019). Apidima Cave fossils provide earliest evidence of Homo sapiens in Eurasia. Nature, 571(7766), 500-504.